THE THOUSAND AND ONE BOTTLES

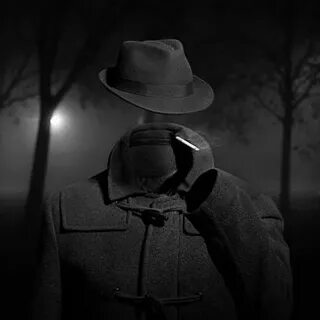

So it became that on the twenty-9th day of February, at the beginning of the thaw, this singular man or woman fell out of infinity into Iping village. Next day his baggage arrived through the slush—and very brilliant baggage it changed into. There have been multiple trunks indeed, together with a rational guy would possibly want, but similarly there had been a container of books—big, fat books, of which some have been just in an incomprehensible handwriting—and a dozen or greater crates, containers, and instances, containing items packed in straw, as it regarded to Hall, tugging with a informal curiosity on the straw—glass bottles. The stranger, muffled in hat, coat, gloves, and wrapper, got here out impatiently to meet Fearen side's cart, while Hall become having a word or so of gossip preparatory to helping bring them in. Out he got here, no longer noticing Fearen side's dog, who changed into sniffing in a dilettante spirit at Hall's legs. "Come along side the ones containers," he said. "I've been ready long sufficient."

And he got here down the stairs in the direction of the tail of the cart as if to put fingers on the smaller crate.

No quicker had Fearenside's dog stuck sight of him, but, than it commenced to bristle and growl savagely, and when he rushed down the stairs it gave an undecided hop, and then sprang immediately at his hand. "Whup!" cried Hall, jumping returned, for he turned into no hero with puppies, and Fearenside howled, "Lie down!" and snatched his whip.

They noticed the canine's enamel had slipped the hand, heard a kick, saw the dog execute a flanking bounce and get home on the stranger's leg, and heard the rip of his trousering. Then the finer cease of Fearenside's whip reached his property, and the dog, yelping with dismay, retreated underneath the wheels of the waggon. It became all of the business of a speedy half-minute. No one spoke, absolutely everyone shouted. The stranger glanced swiftly at his torn glove and at his leg, made as if he could stoop to the latter, then turned and rushed rapidly up the stairs into the inn. They heard him pass headlong across the passage and up the uncarpeted stairs to his bed room.

"You brute, you!" stated Fearenside, hiking off the waggon along with his whip in his hand, at the same time as the dog watched him via the wheel. "Come right here," stated Fearenside—"You'd higher."

Hall had stood gaping. "He wuz bit," said Hall. "I'd higher pass and spot to en," and he trotted after the stranger. He met Mrs. Hall in the passage. "Carrier's darg," he said "bit en."

He went straight upstairs, and the stranger's door being ajar, he driven it open and became coming into without any ceremony, being of a clearly sympathetic turn of thoughts.

The blind turned into down and the room dim. He caught a glimpse of a maximum singular factor, what appeared a handless arm waving in the direction of him, and a face of three large indeterminate spots on white, very like the face of a faded pansy. Then he was struck violently within the chest, hurled back, and the door slammed in his face and locked. It become so speedy that it gave him no time to examine. A waving of indecipherable shapes, a blow, and a concussion. There he stood at the dark little landing, thinking what it is probably that he had seen.

A couple of minutes after, he rejoined the little institution that had formed outside the "Coach and Horses." There became Fearenside telling about it all yet again for the second time; there has been Mrs. Hall pronouncing his dog didn't have no commercial enterprise to chunk her visitors; there was Huxter, the general supplier from over the street, interrogative; and Sandy Wadgers from the forge, judicial; except girls and children, they all saying fatuities: "Wouldn't allow en chunk me, I is aware of"; "'Tasn't proper have such dargs"; "Whad 'e bite 'n for, then?" and so on.

Mr. Hall, looking at them from the steps and listening, determined it excellent that he had seen whatever so very incredible happen upstairs. Besides, his vocabulary turned into altogether too constrained to explicit his impressions.

"He do not want no help, he says," he said in answer to his spouse's inquiry. "We'd better be a-takin' of his luggage in."

"He should have it cauterised straight away," stated Mr. Huxter; "specifically if it's at all infected."

"I'd shoot en, that's what I'd do," stated a woman within the organization.

Suddenly the dog began growling once more.

"Come along," cried an angry voice in the doorway, and there stood the muffled stranger with his collar became up, and his hat-brim bent down. "The sooner you get those matters inside the higher I'll be pleased." It is said by using an nameless bystander that his trousers and gloves have been changed.

"Was you hurt, sir?" said Fearenside. "I'm rare sorry the darg—"

"Not a bit," said the stranger. "Never broke the pores and skin. Hurry up with the ones things."

He then swore to himself, so Mr. Hall asserts.

Directly the first crate became, in accordance together with his guidelines, carried into the parlour, the stranger flung himself upon it with amazing eagerness, and started out to unpack it, scattering the straw with an utter disregard of Mrs. Hall's carpet. And from it he began to produce bottles—little fats bottles containing powders, small and narrow bottles containing coloured and white fluids, fluted blue bottles classified Poison, bottles with round our bodies and slender necks, big green-glass bottles, massive white-glass bottles, bottles with glass stoppers and frosted labels, bottles with satisfactory corks, bottles with bungs, bottles with timber caps, wine bottles, salad-oil bottles—putting them in rows on the chiffonnier, at the mantel, at the desk below the window, spherical the floor, on the bookshelf—everywhere. The chemist's shop in Bramblehurst couldn't boast half such a lot of. Quite a sight it changed into. Crate after crate yielded bottles, till all six had been empty and the table excessive with straw; the only things that got here out of these crates except the bottles had been a number of test-tubes and a carefully packed stability.

And directly the crates were unpacked, the stranger went to the window and started working, no longer troubling within the least about the clutter of straw, the hearth which had long past out, the field of books outside, nor for the trunks and other luggage that had long gone upstairs.

When Mrs. Hall took his dinner in to him, he changed into already so absorbed in his work, pouring little drops out of the bottles into take a look at-tubes, that he did no longer pay attention her until she had swept away the bulk of the straw and put the tray on the desk, with some little emphasis perhaps, seeing the kingdom that the floor turned into in. Then he half of turned his head and without delay grew to become it away again. But she noticed he had eliminated his glasses; they have been beside him at the table, and it seemed to her that his eye sockets were notably hollow. He placed on his spectacles once more, after which grew to become and confronted her. She was about to complain of the straw at the ground when he expected her.

"I desire you would not are available without knocking," he stated in the tone of extraordinary exasperation that regarded so feature of him.

"I knocked, but seemingly—"

"Perhaps you probably did. But in my investigations—my actually very urgent and essential investigations—the slightest disturbance, the jar of a door—I must ask you—"

"Certainly, sir. You can turn the lock if you're like that, you realize. Any time."

"A excellent concept," said the stranger.

"This stror, sir, if I may make so formidable as to statement—"

"Don't. If the straw makes problem placed it down inside the bill." And he mumbled at her—words suspiciously like curses.

He turned into so extraordinary, standing there, so competitive and explosive, bottle in a single hand and test-tube within the different, that Mrs. Hall was quite alarmed. But she turned into a resolute girl. "In which case, I have to want to understand, sir, what you recall—"

"A shilling—put down a shilling. Surely a shilling's enough?"

"So be it," said Mrs. Hall, taking up the table-cloth and beginning to spread it over the table. "If you're glad, of course—"

He became and sat down, with his coat-collar in the direction of her.

All the afternoon he labored with the door locked and, as Mrs. Hall testifies, for the most component in silence. But as soon as there has been a concussion and a sound of bottles ringing together as even though the desk have been hit, and the break of a bottle flung violently down, and then a rapid pacing athwart the room. Fearing "some thing become the matter," she went to the door and listened, no longer worrying to knock.

"I can't move on," he was raving. "I can not cross on. Three hundred thousand, four hundred thousand! The massive multitude! Cheated! All my existence it can take me! ... Patience! Patience indeed! ... Fool! Idiot!"

There turned into a noise of hobnails at the bricks in the bar, and Mrs. Hall had very reluctantly to go away the rest of his soliloquy. When she again the room changed into silent again, store for the faint crepitation of his chair and the occasional clink of a bottle. It turned into all over; the stranger had resumed paintings.

When she took in his tea she noticed damaged glass within the nook of the room beneath the concave reflect, and a golden stain that were carelessly wiped. She referred to as attention to it.

"Put it down in the bill," snapped her tourist. "For God's sake do not worry me. If there may be damage accomplished, placed it down inside the bill," and he went on ticking a list in the workout book earlier than him.

"I'll tell you some thing," stated Fearenside, mysteriously. It become late inside the afternoon, and they have been inside the little beer-save of Iping Hanger.

"Well?" said Teddy Henfrey.

"This chap you're speakme of, what my dog bit. Well—he is black. Leastways, his legs are. I seed through the tear of his trousers and the tear of his glove. You'd have predicted a form of pinky to reveal, wouldn't you? Well—there wasn't none. Just blackness. I inform you, he's as black as my hat."

"My sakes!" stated Henfrey. "It's a rummy case altogether. Why, his nose is as purple as paint!"

"That's proper," said Fearenside. "I knows that. And I inform 'ee what I'm thinking. That marn's a piebald, Teddy. Black here and white there—in patches. And he is ashamed of it. He's a type of half-breed, and the shade's come off patchy as opposed to blending. I've heard of such matters earlier than. And it is the commonplace manner with horses, as someone can see."